Love is in the air, the groom is just “a bit” nervous, the bride is pensive, and the parents on both sides are beaming. The ceremony begins, emotions are high, and everyone is waiting for those unforgettable moments – the ring, lifting of the bride’s veil so she may sip of the wine and, of course, the dramatic breaking of the glass, marking the end of the nuptials and the beginning of a new life, together. But then, in the middle of the Huppah (the name of the traditional Jewish wedding canopy and also used to refer to the ceremony itself), the Rabbi unfurls the Ketubah and reads through it as if nothing else matters.

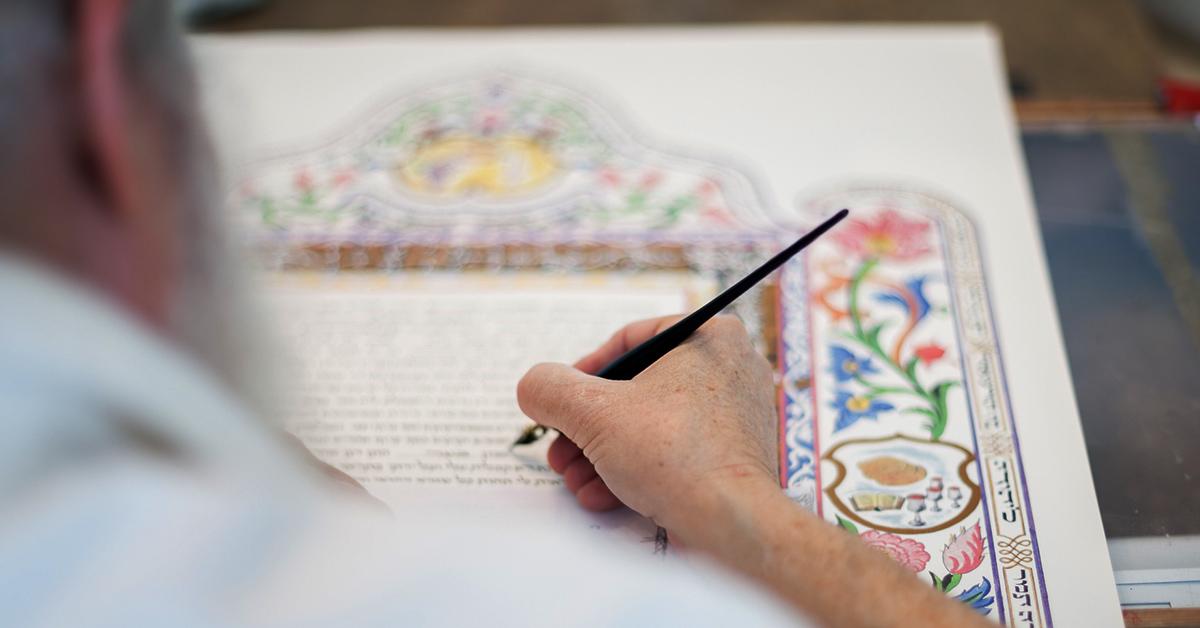

Well, at that moment, maybe nothing else does. When one gets past the magnificent artwork and swirling text, the Ketubah – the Jewish marriage contract, looks beyond the excitement of the wedding, laying the foundations for a faithful marriage and what might happen should feelings between the couple change. It might seem a bit morose to raise the topic of separation in a ceremony dedicated to the love between two people, however, in truth, it reflects the practical, well-grounded wisdom of Judaism, that takes a more wholistic approach, always looking at a lifetime, as opposed to only a single moment.

Today, outside of the ultraorthodox Jewish communities, the Ketubah has become more of a symbolic tradition, and many denominations and individuals have created their own interpretations of this ancient document, as we discuss in this blog post about choosing Ketubot. With that said, we can learn much and more from the original Sephardic and Ashkenazi Ketubah texts (the latter translated here), and we invite you to take a closer look at this most Jewish of contracts.

Roughly two thousand years ago, the Jewish sages of old (Chazal), with some help from the bible – e.g. Exodus 21:10 “… her food, her raiment, and her conjugal rights, shall he not diminish” – understood that love, although most potent of emotions, is not enough to ensure the future of the relationship between man and wife. They realized that existing Jewish matrimonial practices, many assimilated from other religions and cultures, were unjust according to Jewish thought. These led them to devise the Jewish marriage contract, the original pre-nuptial agreement, the “Ketubah” (plural “Ketubot”).

Written in Aramaic, the Ketubah was a revolutionary document at the time, aimed at securing the economic well-being of the wife and her children in case of an unexpected “departure” of the husband through dissolution of the marriage or the husband’s untimely death. This security is achieved by the groom making a monetary pledge of a sum sufficient to support his bride for a period of year after said departure. This commitment is made in front of two witnesses prior to the wedding ceremony, the only signatories to the Ketubah, and the bond is considered absolute, not allowing for any exceptions.

Although not a particularly long document, when we apply a magnifying glass to the Ketubah, we see that it is not “just a contract”, but rather many things that combine to make one of Judaism’s most important texts. The Ketubah is:

OK, only a moment ago we said that the Ketubah “is no just a contract”, but that’s because it is more. With that said, at it’s core it is very much a legal contract. In Israel, it is formally accepted as a legal agreement and in orthodox communities around the world, it is considered “sacred”. This view of the Ketubah as legally binding is a key reason for its creation in the first place and is the reason why it isn’t the newlyweds who sign the Ketubah, rather two adult male Jewish witnesses who must read it thoroughly before signing it.

While the Ketubah itself puts much focus on the financial obligations of a husband in case of departure, a groom also obligates himself to qualitative commitments, such as committing to respect and cherish his wife, to provide for her, to have intimate relations, and more. In fact, the new husband promises not to leave the country without his wife’s approval.

Back to the financial side, the groom does make substantial commitments here as well, mostly that he will pay his wife a specified sum of money called “Mohar” upon ending of the marriage (in the case of death, this obligation carries through to the husband’s estate and inheritors). The sum of the mohar was originally 200 “Zuz” (an ancient coin from Talmudic times). Certain adjustments were made to the Ketubah over the ages to keep the sum to be paid relevant, and today, it is custom to set the amount at an 18th multiple (18 = Hai = life) of NIS / USD 1,000, e.g. NIS 18,000 or NIS 36,000, and to tie this sum to inflation (to the CPI).

In ancient times a woman, including all of her earnings, became the property of her husband upon matrimony*. As mentioned, the primary impetus for The Sages to institute the Ketubah was to ensure that a wife who exits her marriage is not left impoverished, forcing her to forgo her self-respect by needing to beg and making her a burden on the community. This, together with the other stipulations of the Ketubah, serve as protection on multiple plains:

* Note: Owing to the truly ancient origins of the Ketubah, it is a one sided document, where a husband makes commitments to his wife, who, historically, was at a severe disadvantage. As such a document, the Ketubah contains certain notions which should be taken as they are, outdated. With that said, this is not sufficient for many Jewish couples, who choose to use alternate Ketubah texts, some of which can be found here.

We began with mention of how the Ketubah is read in the middle of the wedding ceremony. We didn’t, however, mention that the timing of this reading, and of the Ketubah’s part in the wedding ceremony overall are also carefully planned:

Pre-wedding: Before the wedding even begins, the Ketubah is signed by two ketubah witnesses. Why? It’s simple – no Ketubah, no marriage! The importance of the Ketubah is such, that there is no reason to continue with the wedding without a signed Ketubah.

Mid-wedding: The Ketubah is read in front of the wedding guests at the point during the ceremony that separates between “Kiddushin” and “Nisuin”. Formally, the Jewish wedding is “a process” (yes, marriages are complicated too:) with two distinct stages:

The Kiddushin focuses, although not completely, on the commitments of the bride to the groom. Therefore, it follows quite naturally that the Ketubah be read, outlining the groom’s commitments to the bride, before moving on to the Nissuin.

At the end (or during) the wedding the Rabbi presiding over the ceremony hands the Ketubah to the wife for safekeeping. For the “mahmirim”, strictly observant Jews, cohabitation is only permitted if the wife has the Ketubah in her possession, and it if it is lost, the couple may only resume conjugal life after a replacement Ketubah has been procured.

The earliest known Ketubot were found in Egypt, dated around 440 B.C.E and in Maresha (near Beit Guvrin in Israel), dated around 176 B.C.E. The texts, written in Aramaic, are very similar. Minor changes have been made throughout the years, but the basics have stayed the same, and include (we refer here to the Ashkenazi version and discuss the very few differences in the Sephardic texts later on):

A couple of related, interesting facts:

The similarities between the Ashkenazi and Sephardic Ketubot are much greater than the differences, however, these differences are definitely noteworthy, and you may wish to adopt them in your own Ketubah:

Over the years, many of our clients have told us that an understanding of the Ketubah has made not only their weddings more meaningful, but their marriages as well. We hope that this article has helped you connect more closely to this time honored tradition, and invite you to browse our wide selection of Ketubot, or, for additional information on Ketubot, please visit our “Ketubah Questions” section.