The Ketubah, the ancient Jewish “marriage contract” that, in a sense, formalizes the bond between man and wife, has and continues to be a central part of any Jewish wedding. Historically and traditionally, the Ketubah is a binding legal document that records a groom’s obligations to his bride, including in the case of his death or divorce. Today, more liberal Jewish thinking opts to move away from the traditional texts, preferring Ketubot (plural of Ketubah) that are even handed towards both the groom and the bride and are based in the view of marriage as a pact of love and partnership, not a legal instrument.

Keeping with the Shalom House practice of serving our customers beyond the items for sale on our site (visit our Ketubah selection here), we’re happy to present the following discussion that will, we hope, help you make the best Ketubah decision for you and your wedding.

(see more on “Zuz” below)

Jewish wedding ceremonies are both beautiful and full of meaning, from their transpiring under the canopy of a Huppah, symbolizing the future home to be established by the nuptial couple, to the breaking of the glass at the end of the “hatunah” (wedding in Hebrew), reaffirming commitment to Jerusalem, the Jewish people and God. So too the Ketubah is much more than a decorative document to be signed at a wedding and then framed and hung in the new family’s home, with roots going back thousands of years. Making an informed decision on a Ketubah, therefore, warrants not only understanding the different types of Ketubot one has to choose from today, but also the evolution of the Ketubah over time.

A number of biblical verses speak of a husband’s responsibility to feed, provide for and honor his wife, ideas that gave rise to the concept of a Ketubah. For example, Exodus 21:10 states: “… her food, her raiment, and her conjugal rights, shall he not diminish.”

In addition, in daily biblical life, it was custom amongst the Israelites of the time for the groom’s family to pay the bride’s family a “mohar” , a sum of money or goods, as part of the engagement agreement, to help offset the loss of a pair of working hands (the bride’s, that is). Later, in post-Biblical times, bridal families began offering dowries against the mohar, which itself evolved to be a more complex financial arrangement where a lien was placed against the husband’s property to ensure compensation to the bride in the case of divorce. Eventually, the Ketbuah was devised as a means of recording and ratifying these arrangements, which the wife would safeguard to secure her legal rights should her husband perish or divorce her.

As to physical manifestations of ketubot, the two earliest instances found to date are a ketubah dated around 440 B.C.E. found in Egypt and written on papyrus paper, and an Aramaic ketubah (or draft of a Ketubah) very similar to current day Ketubot, inscribed on clay, found in Maresha (near Beit Guvrin in Israel) and dated somewhere around 176 B.C.E.

In the 1st century B.C.E, the Sanhedrin (the Jewish court system of the time) formalized Ketubah texts, as they were drafted by the then head of the Sanhedrin, Rabbi Shimon ben Shetach. It was written in Aramaic (the “legal language” at the time), and the Talmud devotes an entire book (tractate) to the subject. These texts have remained largely unchanged to this very day, such that people who choose to go with a “conventional” Ketubah are honoring the same tradition as their forebearers.

The fundamental components of the texts are:

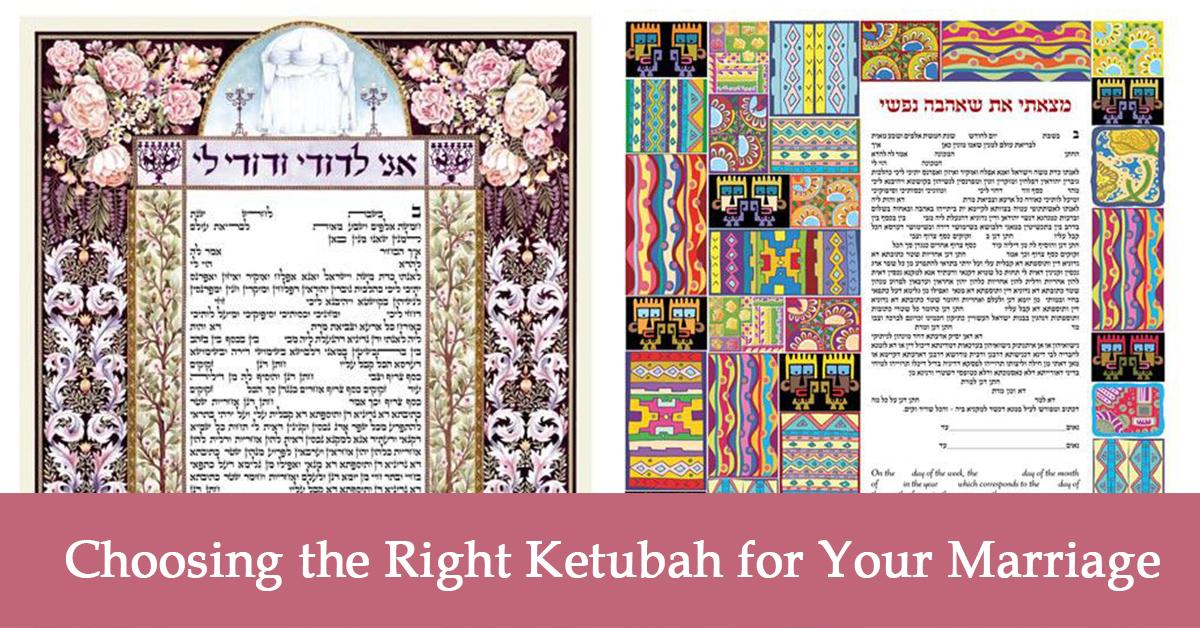

Most of us today are familiar with Ketubot that are graciously adorned with artworks, some to the extent that they are, for all extents and purposes, pieces of art in themselves. The addition of decorative art to Ketubot was born in Italy, in the Jewish settlement of Ancona. Ketubot were adorned with bright colors and gold leaf accents and Biblical scenes were often drawn in the margins.

First, although it lends itself nicely to the section title, it is a mistake to say “THE Modern Day Ketubah”, as there are, at present, quite a few variations, and many often choose to write their own Ketubah. This Ketubah diversity, if you will, has come about in light of Jewish pluralism, more progressive Jewish thinking and an array of alternate lifestyles that have developed in modern day society.

Up until fairly recently, traditional Ketubot were actually quite advanced, as they pertain to the historical status of women and of wives. However, they were, and are, still one sided, written from the male perspective, and they make assumptions that are, for the most part, no longer acceptable or reasonable, e.g. that it is only a husband that can “give” a “get” (divorce) to his wife.

As such, in secular and non-orthodox societies, the traditional Ketubah has largely lost its significance as a legal document. Take, for example, laws in Israel that regulate inheritance and financial relationships between partners, which (mostly), overrule anything written in a Ketubah. However, more liberal Jewish denominations, such as Reform Judaism, secular Jews and interfaith couples, are loath to give up on the Ketubah tradition and have therefore come up with new Ketubah texts that better fit their views and beliefs.

In general, these new alternatives have been adapted to align with the present day view of the martial institution as a partnership rooted in commitment and love for one another. Further, as mentioned above, these Ketubot are about optional pledges the couple wishes to make to one another, not about contractual obligations. They may mention finances, property, rights and responsibilities, but any statement made is on a personal, or rather, interpersonal level, not legal. With this new approach towards Ketubot, we see today not only denominational Ketubot (e.g. Reform Ketubot), but also interfaith Ketubot, LGBT Ketubot, humanist Ketubot, green Ketubot and more. Searching the web yields a slew of prepared texts, as well as options to “create your own Ketubah”.

Well, as you can see, your decision would have much easier 200 years ago, but that’s the problem and the blessing of progress, of having some many more options. With that said, we would like to summarize by listing a few things to keep in mind when trying to select a Ketubah.

Once you have made your decisions, however, Shalom House is your destination for the rest of the Ketubah selection process. We have compiled a large and handsome selection of Ketubot at Shalom House, offering a number of different templates (texts), including standard, reform, conservative and marriage vows, as well as personalization options.

And one more thing – MAZAL TOV from all of us at Shalom House.